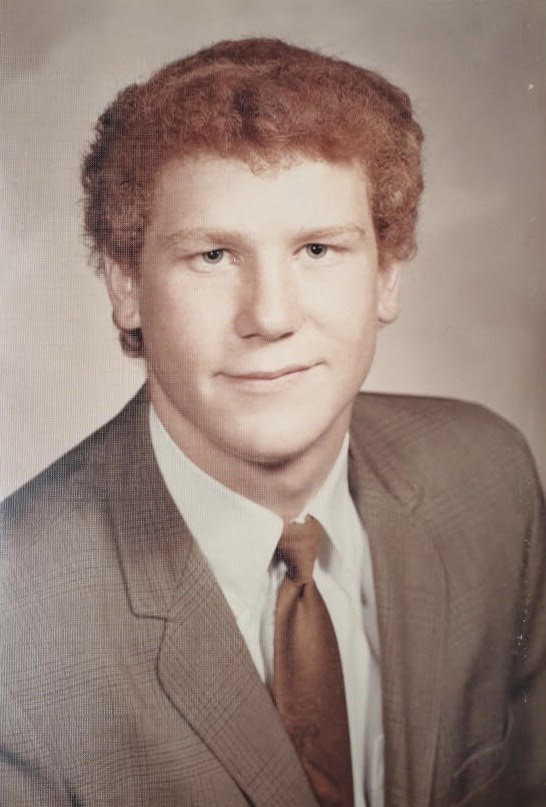

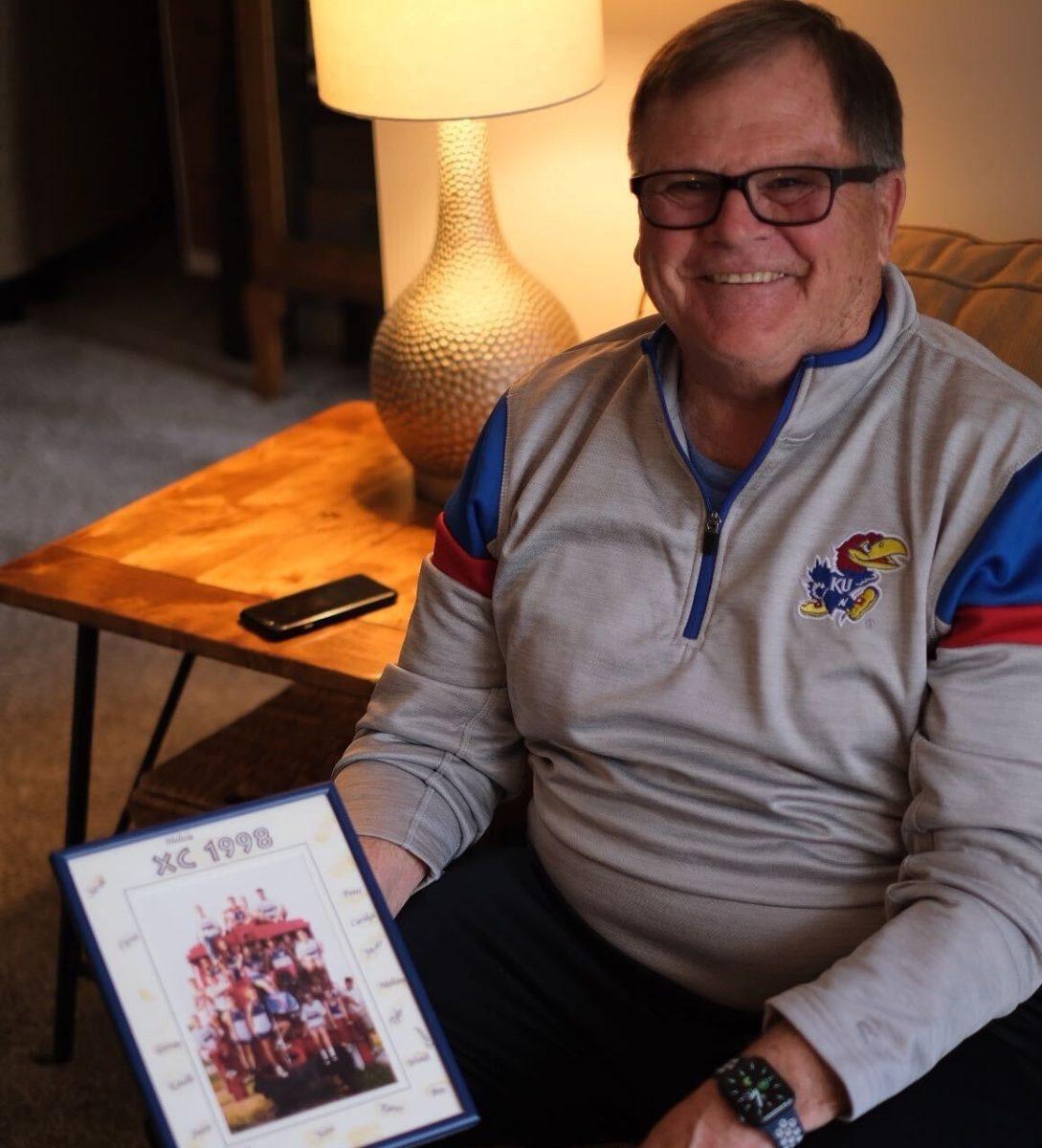

Former athletic director Dave Durkin remembers the girls’ race that won the first individual state championship. It was the 800 for track in 1985.

“I remember [Dawn Henderson] got the baton to anchor the four by four after she’d run the mile, the half and one other race and her legs should’ve been dead.” Durkin said. “We were behind by 20-30 yards. When she got the baton, we knew she was gonna run that girl down.”

He was a coach from 1972, when Title IX was passed as a federal law, until 2010 when he became athletic director. Both roles provided direct insight into the evolution of girls sports in recent decades.

Durkin’s focus was track and cross country. However, he also coached basketball, and at one time was an assistant coach for football.

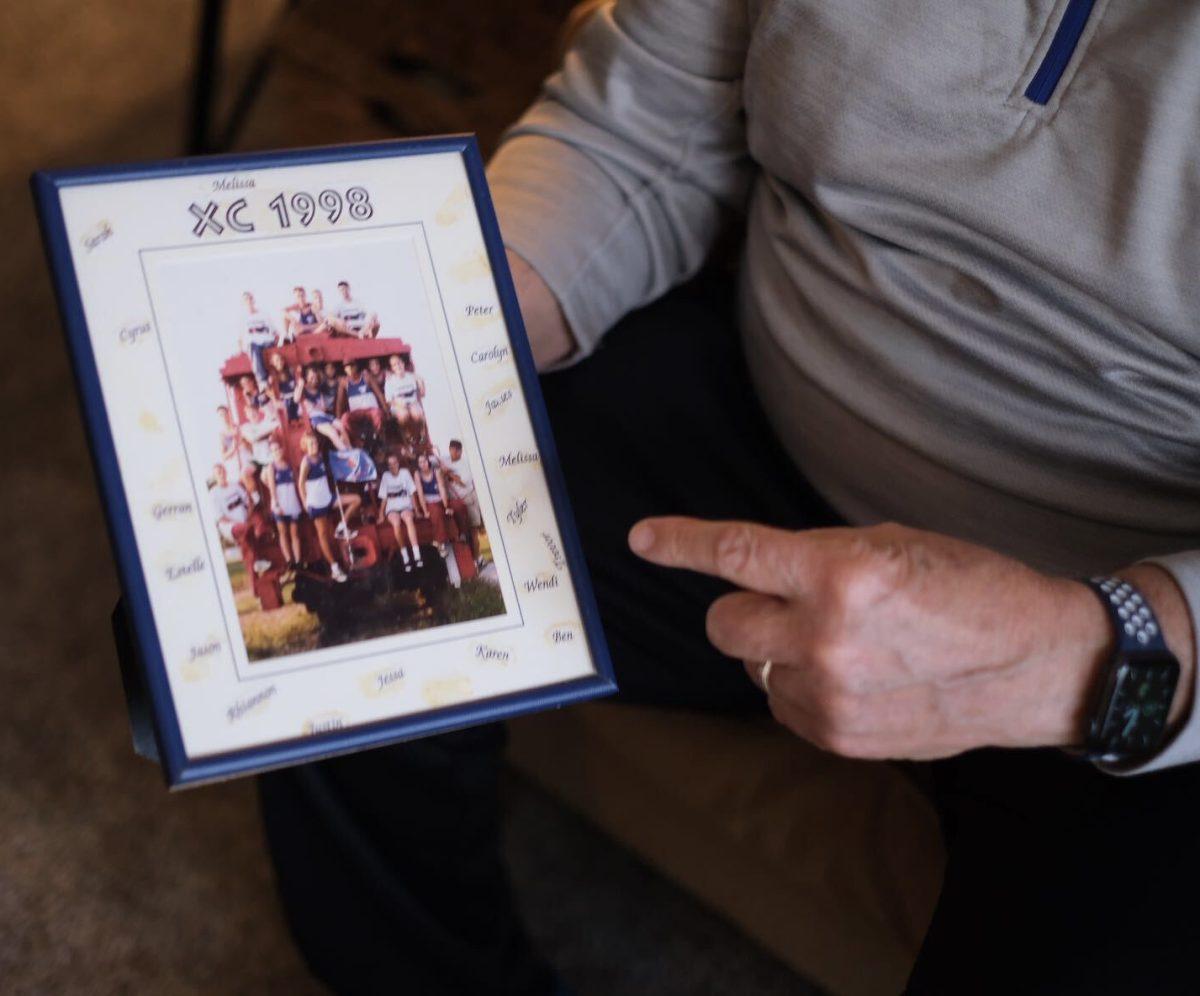

In 1976, the runners practiced on a dirt track where the new Casey’s is now. Durkin said for the first few years there were only a couple of girls in cross country in 1980 when they first started, but by 1994 girls cross country were state runners-up.

Durkin said all of his female athletes worked just as hard, if not harder than their male counterparts.

“The boys had started before the girls, and they hadn’t done anything up to then,” Durkin said.

The transition to athletic director proved to be a big change for Durkin. The job covers everything activity related, including sports, cheerleading, dance, debate, forensics, FFA, band and choir.

“When you’re coaching a sport, you want everything for your kids and when you’re the athletic director, you want it for everybody,” Durkin said.

He doesn’t recall any conversations that took place in 1972 when Title IX was passed. Girls’ sports began to develop slowly and participation was the first hurdle to get over.

Cara Kimberlin took over the position in 2011 but started in the district as a coach for softball, basketball and volleyball. Kimberlin said now it’s her job to get all activities the resources they need to function best.

Kimberlin said Title IX makes her job easier with equal distribution of funds. When both the girls and boys basketball teams made it to state, there wasn’t any difference in what they received in terms of hotel and resources.

Durkin said he remembers the tough part came through non-negotiable needs, such as paying for the annual football helmet safety checks. In his time as athletic director, he sometimes found his hands tied for providing resources for teams, even though all of the uniform purchases happen in fair cycles.

“You have to give them the tools to be successful to work with the kids and same with the kids,” he said. “You sure wouldn’t wanna give something to the baseball team and nothing to the softball team.”

In his time at Eudora, Durkin said there was no fundraising for individual sports, even until 2010. Adding teams to the school was a task.

To add a sport or activity at either high school or middle school, there is now criteria that has to take place, Kimberlin said. First, it has to fund itself for a couple of years, then there is split funding between the district and the program, and eventually the district takes over all funding.

“The reason they did that was that by doing that, you know that there’s a vested interest in continuing that program, not only starting but continuing,” Kimberlin said.

Durkin was the athletic director when soccer first started at Eudora and was co-ed. He said the starting lineup included several girls, but there weren’t enough girls to start a separate team.

After Darren Erpelding came along, the girls team was competing by spring season in 2018.

Erpelding is the boys and girls head soccer coach and said a big reason he came to Eudora was to get a girls soccer program started as he had two of his own girls on their way. He started the girls team for De Soto, too.

“Coming here, we wanted our daughters to play and if [the proposal] didn’t pass the board at the time, we were going to push Title IX in the fact that it’s an inequity. Having a girls soccer team is important,” Erpelding said.

He said he coaches boys and girls differently and that while the boys think he doesn’t make the girls run as much, it’s not the case.

“I hold them to the same standard. I just do it differently,” Erpelding said.

One contributing factor Erpelding attributes his different coaching styles to is the fact that he has more multi-sport athletes on the girls soccer team than on the boys team.

“Some do play three sports, and they are playing in club sports, too. It’s a lot of wear and tear on the body,” Erpelding said. “As coaches, we have to understand that and sit there and say, ‘Yes, we want high school to come first, but we have to be flexible in my opinion at this level 4A.’”

Title IX today

The Kansas State High School Activities Association takes Title IX seriously, said Fran Martin, assistant executive director.

She considers herself “one of the lucky ones.” While Martin was able to compete in high school and continue on to play basketball and run track at a collegiate level, this was not the case for many of her co-workers.

“Many of my colleagues were pre-1972 and the only opportunities they had was maybe club tennis, but there was not anything competitive where they could go play a championship or a state event,” Martin said. “It certainly was not organized by the activities association.”

Martin said there are still things that aren’t equitable at a higher level. However, at the high school level, even when girls wrestling or basketball doesn’t have the same attendance as other sports, KSHSAA does everything it can to treat all activities identically.

“Our primary role is education and that is making sure that our schools understand the tenants of Title IX and the requirements of Title IX in their facilities,” Martin said. “And making sure they know the responsibilities as a federal law.”

Kimberlin said turnout for sports is dependent on what program it is, and football, for example, always gets a crowd of support.

“Or, you know, people that come watch wrestling, dig wrestling, they like wrestling or they wrestled when they were in high school. It’s a certain crowd that comes to something like that,” Kimberlin said. “The important piece, from my standpoint, is that everything gets promoted the same.”

Durkin said he doesn’t see a large difference in the turnout for girls and boys sports and that Eudora is a highly supportive place. Former basketball coach and superintendent Don Grosdidier agreed.

Regardless of turnout, Grosdidier said sports are a special kind of classroom that should be open to all people.

“I just think that there are lessons in life that can be learned from sports that you can’t get easily anywhere else. We want kids to be able to learn not only to win, what it takes to be successful,” Grosdidier said. “There’s a lot to be learned from learning how to lose, losing gracefully and dealing with disappointment and coming back from it. I think that’s what, you know, truly Title IX is about.”

He said established long-term coaches are key to the success of girls athletics. He became the varsity girls coach for 12 years, from 1989 to 2001.

He said he’s noticed some improvement in equality in girls’ sports. When he was an athlete at Eudora, girls practiced at inconveniently late times, he said, but now, they often alternate with boys teams for practice times.

The summer camps were also heavily restricted for girls’ teams, Grosdidier said. Now, girls’ summer training has far fewer rules. Grosdidier doesn’t see a difference in the commitment between girl and boy athletes, and he doesn’t recall coaching differently, either.

“You know, I probably coached them about as hard as I coached boys and football. And they worked extremely hard and were dedicated. I don’t think there were a lot of differences, you know, maybe the style of play was a little bit different,” he said.

The importance of inclusion

Grosdidier said he’s starting to see more women in sports at every level.

“You’re seeing more girls in coaching roles. You’re seeing more woman officials. You’re seeing more woman broadcasters. I think that’s what girls need to see to realize that those opportunities are available for them,” Grosdidier said. “Back in the ‘90s, we weren’t seeing any of that.”

Martin said the majority of the girls teams in KSHSAA are coached by men, not women, and the same is true at a collegiate level.

Kimberlin finds collegiate and professional sports have an influence on her female athletes.

“I think the visibility college sports is now getting on social media and on TV is huge. Years ago, you might get to see the girls NCAA National Basketball Championship Final Four rounds,” Kimberlin said. “Now, every single game is on television. You can watch every single year.”

While Kimberlin doesn’t teach about Title IX to her students, she said being asked about Title IX has made her pay more attention to the distribution of sports and genders she sees on TV.

“I would hope that something that took place 50 years ago, in a way, doesn’t have to be thought about now, because it’s just naturally happening on all levels,” Kimberlin said. “But you want to be aware of it. Hopefully our kids are aware that it had to take place to get it to happen, that these kids’ grandmothers probably didn’t have the same opportunities they do. They should understand that.”

Reach reporter Daisy Bolin at [email protected].

Here are the other stories in the series that have published:

Part 1: Eudora wrestlers aim to be on the right side of history

Part 2: Why Title IX matters in 2022

Part 3: Eudora alumni discuss history of girls sports

Part 4: How 1970s athletes paved the way for EHS girls today

Here is what’s to come:

Part 6: Former Eudora athletes discuss their memories and the influence of participating in sports.

Part 7: Athletes from state championship teams discuss their place in history.

Part 8: We hear from current team captains.

Part 9: Young girls explore what participating in sports means to them.

Part 10: Standing up for Title IX

Dave Durkin reminisces about coaching girls in cross country and track before becoming athletic director.