Mindy Andrasevits pinned it down to one call that taught her what being a first-responder is all about.

It was her second year in the fire service, 1997, in St. Joseph, Missouri.

She’d witnessed catastrophic accidents and many dangerous fires, but it was seeing the wife of an elderly man who fell that she can’t forget.

The injured man was the caretaker of his wife. Had the team not paid attention after loading the man into the ambulance, they could have left her alone, unable to do anything on her own.

“A lot of what we do is about who’s left behind. It’s not just about the patient,” Andrasevits said. “I remember that all the time.”

Now, five months into working as fire chief in Eudora, Andrasevits’ compassion is clear in her work, firefighters said.

Jake Long is a firefighter at North Kansas City and has been a volunteer firefighter in Eudora since 2016. He sat on the panel that interviewed Andrasevits.

Aside from being the most professional interview he’s seen, he said Andrasevits has thoughts that many others don’t usually have, like checking in with a family and explaining what’s next for them.

“Where I see a patient, she sees a person,” Long said. “She’s concerned with their well-being, and not in the short term.”

Andrasevits’ job is 24/7 in Eudora. The team is made up of her, Assistant Chief Chris Hull, one full-time firefighter and 40 active volunteers. The station responds to 50-70 calls per month.

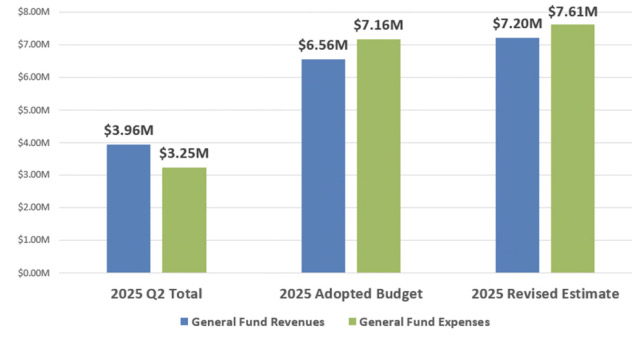

Her responsibilities as chief are less physical than as a firefighter, managing the budget and working on projects as “a piece of the city pie,” she said.

However, Andrasevits likes that it’s not out of the question that she would be on a hose line with the firefighters going into a burning home.

She said smaller towns typically have stations that work this way, frequently taking calls from home and volunteers working often. Long said they’re good at taking care of each other, neighbor helping neighbor.

“I remember thinking to myself as I left driving over the railroad tracks, ‘Gosh, if I made it through this interview process and they offer it to me, I’m takin’ it,’” Andrasevits said.

It wasn’t just her moving — her wife Krista Kiger and her two grandchildren they are raising would be moving to Eudora, too. Kiger has been a pastor for 30 years and now commutes as an interim pastor for First Presbyterian Church in Leavenworth.

“It’s tough to be a woman in the fire service, and in any vocation that’s generally men only,” Kiger said. “The opportunity to be a chief was one that we both said, ‘You’ve got to do it.’”

A picture of their two “little pistols” hangs in Andrasevits’ office next to sticky notes and fire schedules. Both kids love visiting the fire station, Kiger said, and Andrasevits brings her same sense of service into their home.

“If the kids have chores, she teaches that sense of you gotta do a job, you’ve gotta do it well, you’ve gotta do it completely,” Kiger said.

They’ve discovered that Eudora is a family friendly place and the elementary school has been especially responsive to the kids’ needs throughout the adjustment, Kiger said.

A path to firefighting: “Let me tell you about it”

Eudora reminds Andrasevits of where she grew up, Sheridan, Missouri, where she was known as “Mimi” to her family and is the youngest of five. She’s always been a “health nut,” her oldest brother Matt Wilson said.

Wilson is 11 years older than his sister and lives in St. Joseph running a trucking business — the two talk every week.

“She didn’t go through the wild years like a lot of us did. She’s always been focused,” Wilson said. “She’s early to bed, early to rise. You hire her, she’s gonna give you 110%.”

Andrasevits was always the first girl picked for kickball, ran long distances for fun and won weightlifting events. She’s also been a marathon and Ultrarunner since she was 24, running 50k’s and 50-milers.

“It’s 85% mental,” Andrasevits said. “Anyone could train to do it physically. It’s about staying healthy mentally. You can’t let the thoughts creep in that you’re tired or you’re gonna die or it’s too dark.”

She’s run as much as 66 miles in a day. She’s been chased by moose and lost in mountain tops running. She’s dodged rattlesnakes and been followed by coyotes in the desert and dive bombed by bats while mountain running in the dark.

Her mental toughness prevails and her itch for a physical challenge is what brought her to the fire service to begin with.

Before 1996, Andrasevits was an art teacher. She has a degree in art education from Missouri Western State University.

“She was the first to go to college in our family,” Wilson said.

One school day in 1995, Andrasevits had one of her students deliver a sticky note to a substitute teacher who worked as a firefighter. He returned her inquiry with a sticky note that said, “Let me tell you about it.”

A year later, she was the first female firefighter in St. Joseph and taking the job didn’t come without making a wake. Fire stations were built for men, and this station was no different from bathrooms to bunk rooms to culture.

“[Women] are watched differently,” Andrasevits said. “If you make a mistake, it’s not ‘you made a mistake.’ It’s, ‘See, I told ya women shouldn’t be doing this.’”

It took a year before she felt at home in the station, but she felt for the guys since “change is tough.” Despite facing the harsh acclimation women often see in the fire service, Andrasevits earned nicknames, one being “Attic Rat.”

Being 5’5 and 110 pounds (when soaking wet) at the time, and the fact that she’s never been afraid of confined spaces came in handy. She would be hoisted up into cramped dark ceilings to search for hotspots or traveling fire at a time before thermal imaging cameras.

Sleeping an arm’s length away from her male co-workers on the 24-hour shifts made room for her to learn about the brother bond that happens. She exchanged life stories, home struggles and formed many friendships.

Wilson said the St. Joseph firefighters he knows still ask about Andrasevits all the time.

In 2003, she moved to North Kansas City Fire and had a side-gig painting houses and murals. When Valspar Paint had a job opening in Palm Springs near her sister, Andrasevits said, “It felt like it was meant to be.”

In 2008, she left the fire service for eight years.

Although she didn’t anticipate returning to the service, the service came calling when Andrasevits got back to St. Joseph and was asked to work as fire inspector investigator in 2017.

At the same time, she worked on her master’s in public administration/emergency services management.

It wasn’t long before she applied for fire chief in numerous cities, and Eudora was the one that felt like home.

“I look forward to coming to work every day,” Andrasevits said.

So far she’s worked on items she could get done immediately, like policy procedure updates, planning long-term projects and managing the budget. Currently, Andrasevits is working on reconstructing the inspection process for businesses around town.

Her current goal as chief is to build upon the present culture of professionalism, dedication and training.

Firefighters give up their time with family and friends to serve their community and protect lives, she said, and it’s her job to retain their passion and make sure they have what they need, including quality training, education and respect.

In April, Andrasevits will speak on a panel representing women in the fire service. Her advice to anyone in life, something she wants for her kids to grow up knowing, is to know yourself.

“Know yourself really really well,” Andrasevits said. “Because if you don’t know who you are and what triggers you, what upsets you, what makes you happy, then you become a victim of life.”

Reach reporter Daisy Bolin at [email protected].

Submitted photo. Andrasevits describes herself as growing up as a gym rat. In 1999, she won her age and weight class in a powerlifting competition.