A new book highlights Eudora’s historically Black community and how one woman’s life path intersected with the town.

Venecia Eubanks Sutton Price’s book, “Beth Fortner Moseley: Her Story,” was published in February.

Price, a Crosby, Texas, resident, has always had an interest in her family’s history, and this project that focuses on her Aunt Beth Fortner Moseley’s life has been years in the making.

Her aunt lived in Eudora from 1917 to 1923, before moving to Kansas City and Tulsa, Oklahoma.

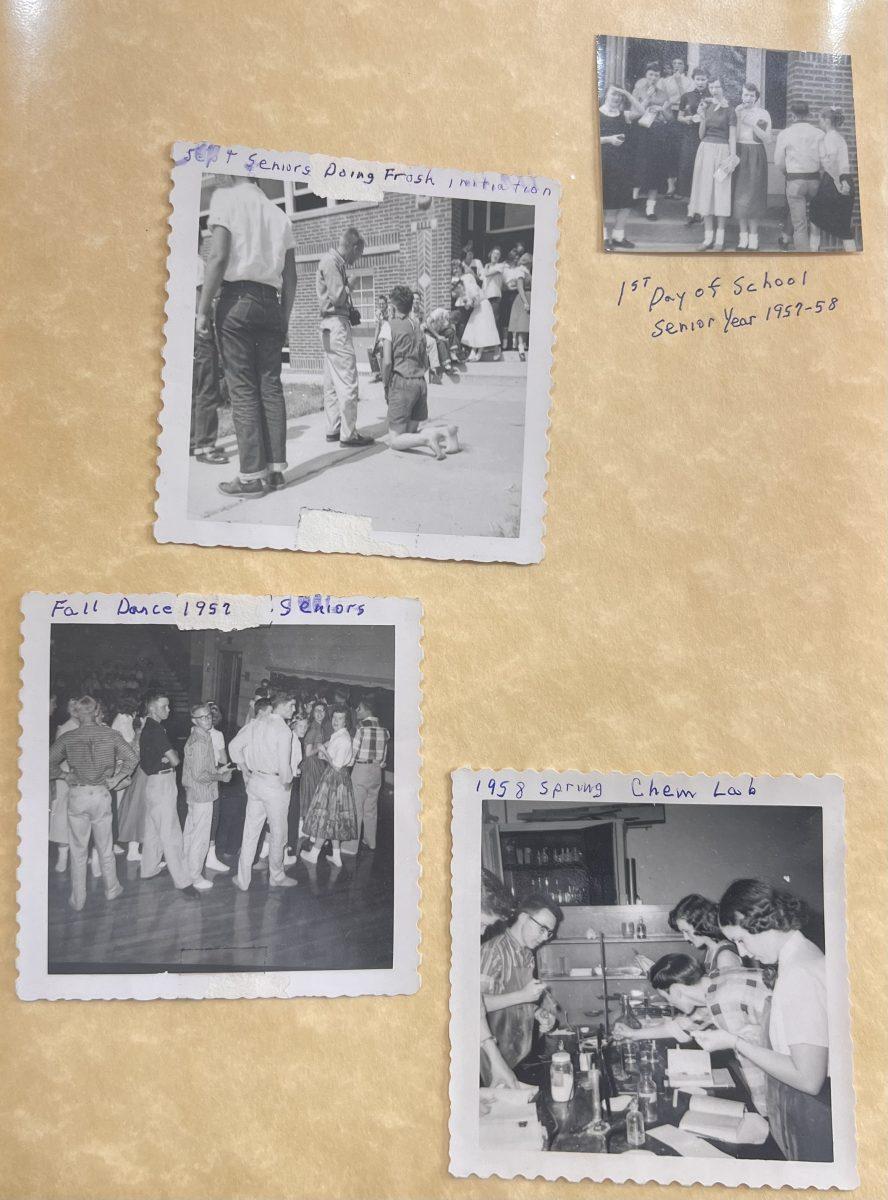

Price started putting together the book in 2021, but the beginning of this project stretches back 18 years, when her aunt died and Price’s family traveled to Chicago to collect her personal items.

“I put them in a box, and I shipped them back home to Texas,” Price said. “I fully intended to go through them. And then my brother passed away a month later. And so I went to Detroit and gathered his things, and shipped them to Texas again. When I got back, I was just kind of emotionally not ready to go through them.”

Price said life got in the way, but she eventually read her aunt’s writings when her husband decided to write about her grandfather and asked her to look for relevant papers.

“I opened the box that had my Aunt Beth’s things in them, and I just sat there and read them,” Price said. “I was just overwhelmed and immediately said, ‘This is a book.’”

As Price went through her aunt’s writings, she remembered stories she had heard as a child.

“When I read my Aunt Beth’s things, it fit a lot with what I had heard from like my parents and so forth growing up,” Price said. “So I guess the biggest challenge was just emotionally putting it all together. The challenge is more of how to weave it together, and not overrun her story with what I was adding.”

Price was also struck by similarities between their lives. For example, Price attended many of the same schools as her aunt, as they both grew up in Tulsa.

Another similarity was their celebration of Emancipation Day, also known as Juneteenth. As Price has spent most of her life in both Oklahoma and Texas, she knew the holiday by its latter name, but found the description of celebrations extremely similar.

Fortner-Moseley does not refer to race relations often in her writings about Eudora, where she spent a large part of her childhood.

Price found this was different from what her grandfather, Fortner-Moseley’s father, experienced while living in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Tulsa was the site of a race massacre in 1921, where dozens of Black people were killed, with their homes and businesses destroyed as well.

Price said that by looking back on this history, both the good and the bad, one can gain a deeper understanding of other communities.

“I would think that people, from Eudora especially, might be pleasantly surprised at how, at least this family’s experience, was so favorable,” Price said. “I also think that by looking back, and seeing how things were— the good, the bad and the ugly—can just give a better perspective on moving forward.”

Ben Terwilliger, executive director of the Eudora Community Museum, said Eudora’s Black community primarily began to form after the Civil War, when slaves in Missouri were freed and some came across the border.

“They didn’t really have any money or much to start out with, so a lot of them were tenant farmers or laborers,” Terwilliger said. “Eudora was a segregated community. There were incidents of racial violence, a branch of the Ku Klux Klan was active in Eudora in 1924. It would have been a very challenging life.”

Terwilliger said much of Eudora’s history was written by the town’s white families over 50 years ago. He added that most of Eudora’s Black community had left at that point.

Terwilliger attributes this to the Great Migration, when Black people in rural places moved north for better-paying jobs.

“Within the last 20 years, people had started to look into Eudora’s Black community, but the problem was anything that was written before really had nothing to go on,” Terwilliger said.

Terwilliger said he was glad to see a book that highlights the city’s Black history.

“I was happy to see a more in-depth book on just what the day-to-day lives were like for Eudora’s Black community 100 years ago,” Terwilliger said.

Stephanie Jones, secretary of the Eudora Historical Society, has spent years researching Eudora’s historic Southwest City Cemetery. Much of Eudora’s Black community was buried there.

Jones said the cemetery is no longer in its former state, as headstones have been disturbed and plant growth has obscured many of them. She applied for a grant in 2020 to do more research on the site, but was not awarded any money.

Jones planned to increase the amount of signage in the cemetery and possibly work with local people who know how to use ground penetrating radar, as the number of people buried there is unknown.

“Between vandals and people not considering the cemetery – I was always taught that cemeteries are sacred ground, and that’s important to me,” Jones said. “So I’m continuing my research and there’s a lot of rabbit holes you can go down and end up getting no information.”

Jones encouraged community members to reach out to her if they have any connections to the Southwest City Cemetery or memories of the Black community as she continues her research.

“You know, people in the community perhaps knew someone that had a relative buried there, I mean, there’s a lot of people that may have a history of going to school with people and know where they moved to,” she said.

Price had a similar challenge with finding information while researching her ancestral history. Records for Black families can often be unavailable due to slavery or the institutional racism that pervaded the country well past slavery.

Price said one lesson she learned from this process is to start writing her own personal history, and she encourages others to do the same.

She also encourages others to interview elders in your family or community. Recording someone’s oral history can help future historians and help a loved one’s family remember them once they pass away.

In terms of the research Price completed, she said she used a variety of resources, including Newspapers.com and Genealogybank. She also visited Eudora years ago to walk where her ancestors once did.

“In 2011, I went to Eudora. I went to the [family’s] house across from the lumberyard. I went to the cemetery, I went downtown and, you know, just kind of walked around and stuck my head in a few places. I went to the library,” Price said.

Price added that the positive and helpful reception she received from Eudora, Lawrence and Douglas County residents was different from what she had experienced in other parts of the country. She spent time in the South researching her father’s family history.

“My thing has always been to honor my ancestors,” Price said. “And my husband is also doing the same thing. We’re kind of the generation where he and I feel the obligation to document so that we can pass on [the history.] I feel like only when you know where you’ve been can you figure out where you really need to go.”

Price donated a copy of “Beth Fortner Moseley: Her Story” to the Eudora Community Museum, which is available for community members to check out.

Reach reporter Abby Shepherd at [email protected]