This is the fifth story in a weeklong series examining the pending arrival of Panasonic. We also created a printed newspaper special section that is on sale now. Watch our Facebook page for where and when we will have copies available.

State health and environment officials have so far identified few environmental risks posed by the Panasonic plant’s production of lithium-ion batteries for electric cars.

However, lithium ions, a main component in Panasonic’s rechargeable car batteries, do raise new concerns for firefighters. Lithium-ion fires burn differently and are often harder to control than regular fires. Local fire departments are already studying new ways to deal with the dangers.

The environmental impact will also be bigger and broader than just what chemical compounds go into and out of the Panasonic plant, said University of Kansas associate professor Ward Lyles, who specializes in urban planning. Panasonic’s arrival will spur more industrial, commercial and residential growth that will affect surrounding towns in numerous ways, he said.

The Eudora Times found out what this plant may mean for your environment.

State oversight

Strict environmental laws and modern anti-pollution equipment will protect the air, said Rick Brunetti, director of the Bureau of Air with the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. He said there is no threat of a toxic plume in an industrial accident. Similar regulatory protections are in place to prevent water pollution.

The main concern for state air pollution regulators will be the plant’s emissions of volatile organic compounds, which are produced in small amounts when cooling the batteries inside the plant, Brunetti said.

Volatile organic compounds are industrial chemicals that evaporate and contribute to the formation of ground-level ozone when they react with nitrogen oxides in sunlight. Ozone is a main ingredient in smog and can be harmful to people with respiratory problems.

Brunetti said modern manufacturing processes will help limit emissions. The plant will produce no greenhouse gasses, sulfur dioxides or nitrous oxides, he said. He also said he has no concerns about the use of lithium ions in the plant.

The Kansas Bureau of Air is currently reviewing a permit application that would ensure the plant complies with all requirements of the federal Clean Air Act. The bureau is also reviewing the best control mechanisms and pollution equipment to combat potential pollutants.

Tom Stiles, director of the state’s Bureau of Water, said the bureau’s concerns lie in the flow of wastewater from the plant into De Soto. He said the bureau is working with De Soto on a biweekly basis to prepare wastewater plants for possible expansion and for additional pollutants within the wastewater.

He said the plant will likely have an industrial stormwater permit that will govern runoff and isolate the exposure of water to materials deemed pollutants. He said there is no likelihood of wastewater being deposited in the Kansas River, but is not sure how the wastewater stream will look.

He said the bureau does not expect to see any type of aggravated contamination move into Kill Creek or other areas.

Concerns from fire chiefs

One of the biggest fire concerns with lithium ions is thermal runaway, which occurs when battery cells reach uncontrollable self-heating states and is difficult to stop or control, De Soto Fire Chief Todd Maxton said.

Another is the release of toxic hydrogen fluoride when lithium ions burn, said Eudora Fire Chief Mindy Andrasevits. The gas could potentially injure firefighters on the scene but depletes quickly into the air, so there is little risk of toxic plumes, she added.

Lithium-ion fires also require large amounts of water to extinguish.

This is especially a problem in figuring out how to put out electric car fires on the highway, where fire hydrants aren’t accessible. Andrasevits said it would take 10,000 to 30,000 gallons of water to extinguish an electric vehicle fire, but De Soto and Eudora’s fire trucks only hold approximately 1,000 gallons.

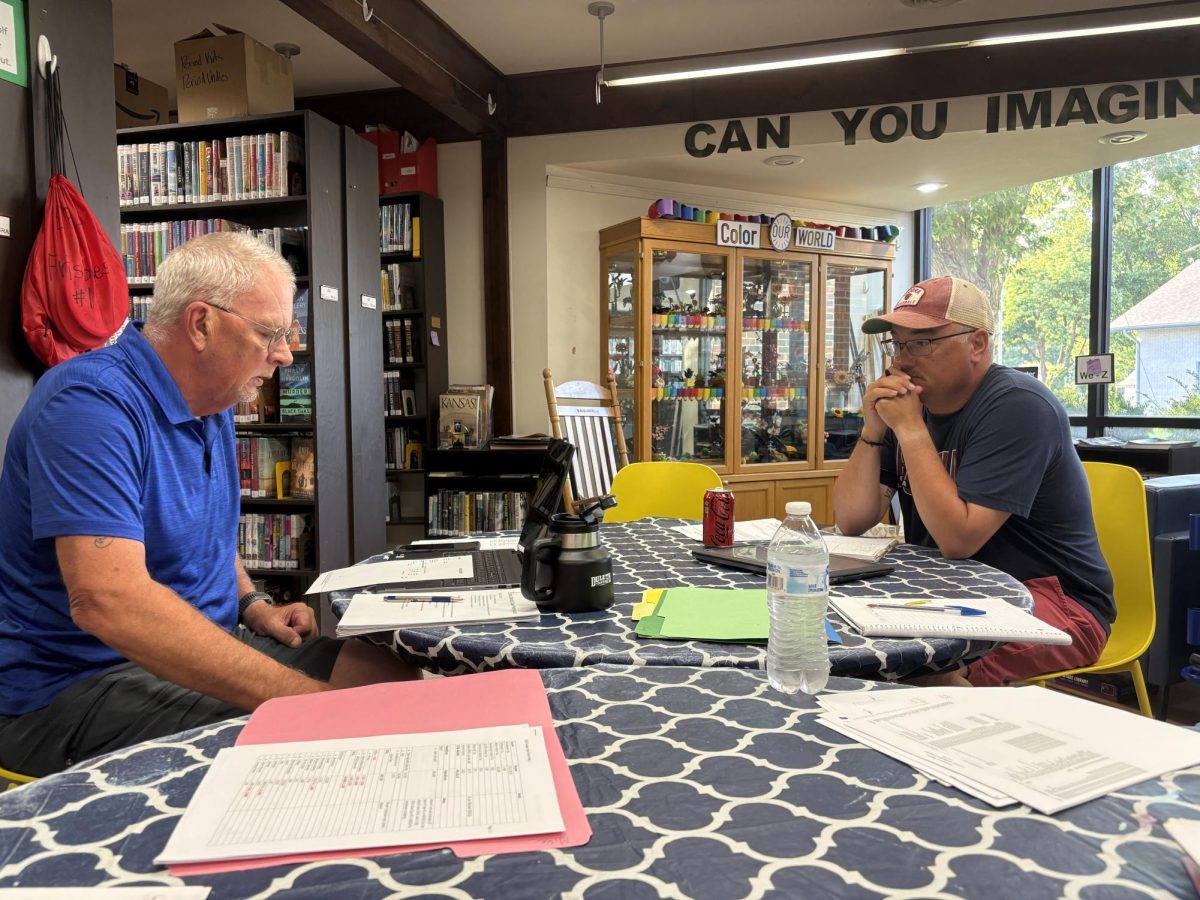

Maxton said they are conducting a needs assessment of the department, which includes creating an online training plan where firefighters can practice fighting lithium-ion fires and vehicle fires, possible expansion of the department and possibly purchasing additional equipment.

He said they are still waiting to hear from their partners about what the department may need, and it is too preliminary to make decisions without more information.

His department is in regular contact with the Storey County Fire Protection District in Nevada, where Panasonic produces electric vehicle batteries inside a Tesla plant, and noted the Nevada plant is different from the De Soto plant.

“We’re not sure yet if we’re comparing apples to apples,” Maxton said. “It’s not just the battery production facility. It’s also the downstream suppliers.”

Andrasevits said her department has trained with lithium-ion vehicle fires for several years and plans to do joint education and training with the De Soto fire department.

She said the department is not, at this point, planning to purchase new fire equipment. But she said growth from the Panasonic plant and from a proposed Eudora sports arena would inevitably increase the need for more firefighters and first responders.

This could include transitioning from a mostly volunteer department to a fully paid department, building a new station and increasing apparatus.

Andrasevits’s department expects to see an increase in call volume and to respond to calls at the Panasonic plant along with the De Soto department if they require mutual aid.

Regional impacts

Although the Panasonic plant is supplying a key source of green energy, it also will produce cascading and secondary environmental effects on the region that have not been fully considered, KU’s Lyles said.

“The framing is so focused in marginal effects that are direct and on-site,” Lyles said. “But we can’t lose sight of everything that’s environmentally oriented once we leave the boundaries of the project.”

One of Lyles’s main concerns is an influx of trucks, heavy machinery and thousands of new workers driving to and from the plant every day, increasing greenhouse gas emissions and demand for fossil fuels.

Lyles is also concerned about the conversion of more and more farmland in the K-10 corridor into highway, residential or retail properties. Besides the Panasonic plant, a cadre of major suppliers are expected to set up shop, creating more jobs and spurring demands for more housing and amenities.

Besides a loss of wildlife environments, more turf lawns and pavement could increase the likelihood of flooding and more pollution flowing into waterways because they create more impervious surfaces.

“Every time you pave one of those [dirt or gravel roads], that’s more water that’s flowing off with more pollutants,” he said. “So individually, any particular driveway doesn’t seem like a big deal for a creek, but if you put in thousands of driveways and the roads connecting, all the sudden that’s paving over a ton of space.”

Sunflower pollution

Over the 50 years that ammunition was produced intermittently at the Sunflower plant, 53 sites were identified as solid waste management units and were contaminated to some level with hazardous materials, according to a 1998 Johnson County Planning Department Conceptual Land Use Plan.

Groundwater contamination was detected over a limited portion of the site. The main groundwater contaminants are substances resulting from the degradation of propellants, including nitrates, sulfates and metals, according to the U.S. Army Environmental Command.

The Army is increasing its focus on creek and groundwater damage, where waste fluids have been deposited into on-site ponds. The Eudora Times reached out to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Kansas City District for more information, but did not receive a response in time for publication.

The intended site for the future Panasonic plant is cleaned up and released for development, but crews continue to decontaminate other parts of the old Sunflower site to remove metals, nitroglycerin, nitrocellulose, nitroguanidine and nitrates, according to information provided by Philip Harris, a spokesman for the Kansas Bureau of Environmental Remediation.

The entire Sunflower cleanup will not be done until at least 2028, but the decontamination work is not expected to cause any environmental concerns at the Panasonic plant or outside its boundaries, Harris said.

The nearly 3-million-square-foot plant will cover so much surface area it will help prevent rainfall from carrying further pollutants into the groundwater, according to Stiles, director of the state’s Bureau of Water.

“It’s an industrial site,” he said. “So it has tight, new infrastructure that’s resilient to weather conditions.”

Going forward, Lyles said people in Eudora, De Soto and across Johnson and Douglas counties should have central seats at the table in dictating how this growth proceeds.

“If [the growth] is left unregulated, we’re gonna get a bad outcome,” Lyles said. “We’re going to get horrible suburban sprawl that chews up the landscape. Even if every single person on the plant was given a free electric car, so the emissions weren’t there, you still have tremendous land-use setbacks.”

Reach reporter Jenna Barackman at [email protected].