To donate to support our community journalism, please go to this link: tinyurl.com/y4u7stxj

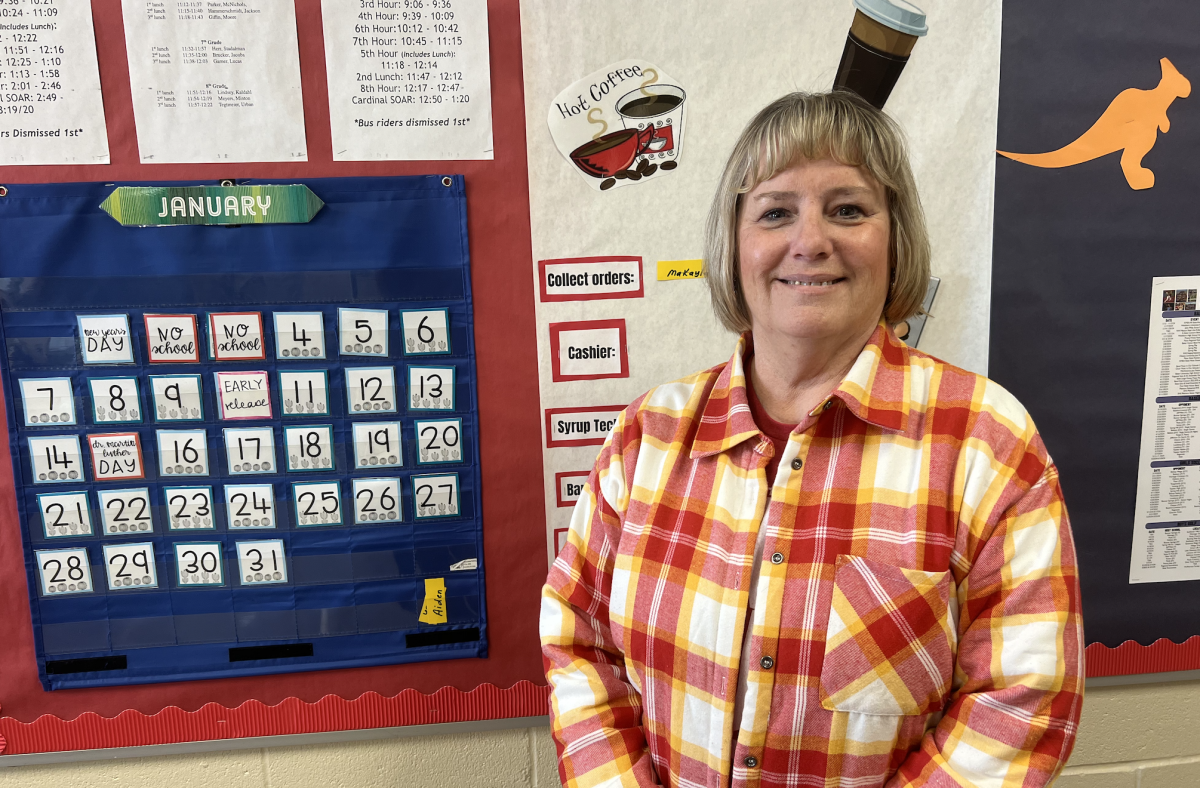

Susan Carnagie has been a paraprofessional in the district for 32 years. Carnagie took the job because of the flexible hours while having children.

This is the first story in a two-part series examining changes in paraprofessionals, special education and substitute teachers since the start of the pandemic.

Susan Carnagie’s job is to help students however she can with the goal that they eventually won’t need her.

Working as a paraprofessional is being a student’s right hand, she said. She’s also a set of eyes and ears for teachers since paras see a lot that teachers just don’t have time to, she said.

A paraprofessional is an education professional who may help students with their work one on one or in small groups, accompany them to classes or make sure they are given special attention when their teachers can’t be with them at all times.

Trying to fill these positions reached a critical point during fall 2021 when the interlocal that provides workers to three school districts only had 96 paras on staff, said Dan Wray, director of the East Central Kansas Cooperative in Education.

The shortfall also came at a time when more students were being identified as needing individualized education plans, or IEPs, Wray said.

About 290 students in Eudora alone – or 17% of the student population – now have some kind of IEP, he said. The majority of those students receive some kind of support, whether from a para in their classes or peer support.

Wray has seen hiring for paraprofessionals improve since the pandemic. However, the battle continues to receive sufficient funding from the state and to ensure there are enough workers.

Overcoming hiring challenges

The East Central Kansas Cooperative in Education provides the school districts in Eudora, Baldwin and Wellsville with paraprofessionals, special education teachers, social workers, therapists and behavior specialists.

Among all three districts, there were 126 paras in mid-January but the number is regularly shifting, Wray said.

Eudora makes up 45% of the students the interlocal caters to, meaning the district has around 65 of the paras.

As of now, the number of paraprofessionals in the interlocal has stabilized, but over-hiring positions is necessary since employees may need time off, maternity leave or leave for other reasons, Wray said.

They also sometimes lose paras to teacher positions, which is encouraged if a para is interested due to the nationwide teacher and specialist shortage.

However, a lot of paras who leave end up coming back, Wray said.

“Every four applicants we get, one of them is someone who is coming back to the interlocal after trying a job in another field and it wasn’t as rewarding or didn’t fit their needs,” he said.

Therefore, to say employment is full doesn’t mean they aren’t still hiring because there is a lot of movement in the position, he said.

The number of paraprofessionals started to rise again in late 2022. The interlocal now has its steadiest numbers since before the pandemic.

To keep up with need, the interlocal raised pay to stay competitive with other districts. The salary schedule now starts at $44,100, with the average salary of certified employees at $54,200. Specialists average around $59,000, Wray said.

He said a big financial challenge is the Legislature not funding special education appropriately.

When lawmakers don’t increase the amount of special education funding that is legally required, the money to pay for federally and state mandated special education has to come out of district general funds.

“That leaves them with little money to increase teacher compensation for general education teachers,” Wray said.

It’s an ongoing cycle, he said.

“We can’t seem to get our footing because the Legislature won’t give us the money that we need,” he said.

A state law says the state is supposed to fund special education costs at 92%, but that requirement has not been met since 2009. Currently, funding is at 67%, he said.

The lack of funding is difficult for paraprofessional providers to navigate as they are expected to fill a wide variety of student needs.

Daily life as a paraprofessional

Paras assist students by scribing for them, offering text to speech, conducting small groups to help them read aloud, take students out of the class for their tests and anything else their IEP determines necessary.

Carnagie has been a paraprofessional in the district for 32 years. She started in the role because of the flexible hours when she was raising kids. Now she has grandkids, and the schedule is still perfect, she said.

Carnagie has worked in Danny Ruegsegger’s life skills classroom at the middle school for about five years. She’s loved her position working with kids.

“They’re just a special place in my heart,” Carnagie said.

In life skills, she gets to help students learn hands-on skills that will follow them into life, like laundry, running the coffee cart and setting up the Cardinal Market. It helps students learn about different jobs and how to work in a work setting, she said.

She helps set goals for students with the help of their parents, their general ed teachers, special ed teachers and administration so they have something to move forward to and can succeed.

She previously worked in several other grades in the district, but life skills has given her more connections with students. She has two students on her full-time caseload and two floater students. Carnagie will serve as the para for these students the entirety of their middle school time.

She spends a good part of her day in Ruegsegger’s class before following students around to other classes like PE and health. She helps students feel included in classes and will participate in class to help her students get involved.

Although technically Carnagie can retire, she has a particular seventh grade student she wants to help until he moves to the high school, she said. After that, she’s not sure if she’ll stay or retire because she loves the kids and her position, she said.

The job is about spending time with the kids, and she wouldn’t be doing it if it was for the money. She said pay is the main reason people aren’t getting into the profession.

Carnagie said she isn’t sure everyone knows the wide range of things paras do with students, and if they were better informed they might be more interested in entering the profession.

“There’s so many rewards to it,” Carnagie said. “When you see the light bulb go off, you’re just ‘Wow,’ you know.”

Right now, she feels the middle school is pretty well-equipped with paras, but she did see paras having to step up and help more kids when the shortages were especially tough.

Above all, Carnagie thinks higher pay is needed for all teachers, and more funding from the state for special education, especially as more students with IEPS are identified.

Ruegsegger has worked in special education since about 2012, first becoming a para in another district and now as a special education teacher. He said a lot of the best paras are young and determined to go into education, or they are people who don’t necessarily need to work but love the kids.

By requiring more training and giving paras higher pay, they would have less turnover and lead to a quality applicant pool, he said.

“You need to make it a higher bar to get the job, and you need to make the job much more desirable,” he said. “I hated leaving my para job because I loved it, but I have three kids.”

The outlook on education

Getting young people in high school to take an interest in special education has also been part of the interlocal’s mission. Eudora has a peer mentoring program to help with this.

“The more that we hear negative things about education in Kansas, the fewer kids will go into education and the reality is education in Kansas, the public education system, is really good,” Wray said.

Wray thinks it’s important to publicize all the good work that Kansas has done, with graduation rates and higher test scores, instead of only discussing the bad.

“So that’s the only thing that we can do is continue to encourage that because that means the education system and the teachers that are involved within providing that education are doing the job that they need to,” he said.

Working with young people, whether they are preschoolers or high schools, whether they have mild learning disabilities or more behavioral challenges, is a rewarding field, he said.

Wray has been in the business for 37 years, and is retiring at the end of the year, but he has always received more out of the job than he has put in it.

“To see the gains that kids make, and to be a part of that and recognize that, that you can make a child’s life better just by being there, that’s what it’s all about. And that’s education. That’s what being paraprofessional is all about,” Wray said.

Some states are lowering requirements for people entering substitute teaching or paraprofessional positions due to smaller applicant pools as a result of the salaries, said Rick Ginsberg, dean of the KU school of education and human sciences.

This is not always a good option, and the solution starts with higher pay, better working environments and greater autonomy for teachers, he said.

Over the last 10 years, there has been a significant decrease in degrees and certificates in high-need specialities, according to the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education.

This includes a 4% decrease in special education, a 27% decrease in science and mathematics education, and a 44% decrease in foreign language.

In Kansas, some universities have experienced declines, but most have held flat with a minimal decline, Ginsberg said, including KU’s teaching department.

The biggest reason for these changes is the pay, he said, but the working environments have also become much more challenging. Some of these issues are due to state laws telling districts what they can and cannot teach, Ginsberg said.

Teachers also are being asked to do things they have never done before, such as helping students with social emotional needs despite a lack of training, he said. They’re also being asked to cover classes when staff is missing.

The National Education Association reported the average starting salary for a teacher is $42,844. In addition, nearly 40% of all full-time education support professionals in K-12 earn less than $25,000 a year.

Kansas isn’t far from the national average, with its starting salary at about $40,130, or 34th in the nation.

Needing support

Part of Wray’s job is to meet with lawmakers and encourage them to support special education more, especially since Gov. Laura Kelly has continued to advocate for this funding.

Wray said Eudora isn’t as short on paras as other areas in the region, which is a sign that Eudora may be doing something right. It doesn’t mean they’re not at risk of falling behind if they don’t keep hiring, he said.

The interlocal has been offering benefits to full-time paras since Wray was hired eight years ago, which has been a move in the right direction, he said.

Getting para subs has proven more difficult. Eudora has had to use teacher subs as paraprofessional subs because there aren’t as many people wanting to be para subs, he said. The requirements for some teacher subs is less and the pay is greater, Wray said.

The problem of finding workers is somewhat of a cyclical issue, Ginsberg said. Some in academia have called this a leaky bucket issue. Even if there are people being trained to enter the field, schools are losing teachers because the work is intense and hard, Ginsberg said.

Although some say teachers don’t work long hours and have time off in the summer, Ginsberg said many are staying up late to work on lesson plans and work long hours in the summer in addition.

“We have this situation that it’s a hard job. The media and politicians and others have made it really, really challenging to stay in it,” he said. “I mean, we’re always being told they’re not doing well enough, and they got to do a better job, etc., etc.”

Young people see how hard the work is and what teachers have to put up with and that they could make substantially more money doing something else, he said.

Teachers get into the job because it’s rewarding, but the low pay might not be enough to keep them in it anymore, he said.

Even in bigger metro districts, the applicant pools are not what they used to be. In positions that used to get 50 applicants, they might only get a handful. Districts don’t have the applicants to be selective in who they hire, Ginsberg said.

“When we have shortages in teaching, what we tend to do is we say, ‘Well, you maybe you don’t need that full education training.’ I mean, there’s some places we’ll let people with a high school degree do that,” Ginsberg said.

Lessening requirements isn’t the solution, he said.

“We want people to be well trained, go into this and have them want to stay because the working conditions are strong. They’re remunerated for what they do, and they’re respected for the work they do,” he said.

There are 3 million teachers in the nation, so the question is if the country is willing to increase pay.

The nation needs to empower teachers to have greater autonomy over the work they do, he said.

“We talked about raising future salaries by giving them three or 5% increases, which are welcoming, great. Double salaries, triple the salaries, then we’ll get those people who are going into other fields,” he said.

Reach reporter Sara Maloney at [email protected].