This is the second story in a five-part series examining the fifth anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts on the lives of area residents. Effects on students, education, athletes, local businesses and public health will be featured.

Although the school district didn’t see drastic changes in standardized testing scores during or after the pandemic, social emotional learning, increased technology use and teacher burnout changed aspects of education.

With this week marking the fifth anniversary of the start of the pandemic, district officials say most lingering issues have since been resolved.

However, Director of School Improvement Heather Hundley said chronic absenteeism remains an issue in all grade levels.

In 2023, the district chronic absentee rate was 16.7% against the state’s 21.82%. In 2024, the rate went down slightly to 14.67% compared to the state’s 19.77%. No chronic absentee data was available for the pandemic school years.

Absenteeism was about 18% at EHS in 2024, 15% at EMS and 13% at EES, all of which are slightly lower than state averages.

The district is continuing to try to make it clear to families why students need to be at school because absences can start to affect students in future grades, Hundley said.

Counselors and school principals discuss how they have navigated education in the years since the pandemic and its impact on students.

Effects on young learners

As part of the kindergarten readiness program, parents complete a questionnaire around development. Some of the things being noted across the state are more students struggling with fine minor skills as students are using technology more since the pandemic.

Making sure learning is play-based helps the youngest students with developing those skills, Hundley said.

The pandemic also highlighted the need for students to have positive relationships with adults, like those created with the middle school mentoring program and the buddy program at the elementary school.

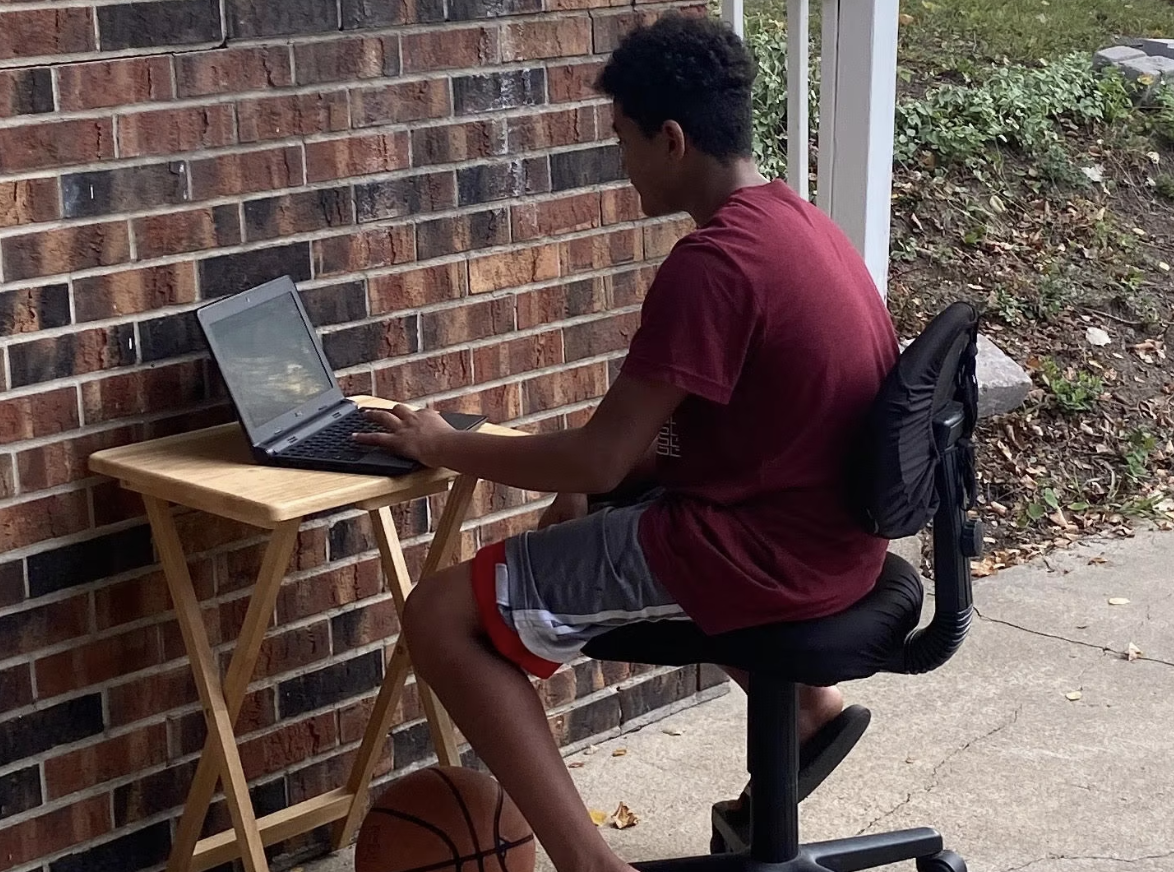

Technology did, however, open up new avenues for teaching, which wasn’t necessarily a priority before covid, she said. There was no opportunity to teach asynchronously like there is now. The pandemic brought need for flexibility, which helped to reevaluate some of the teaching practices.

Elementary school counselor Brenda Wiley has been in the district since 2001 and has seen some changes in social emotional skills since the first pandemic lockdown.

She and Chelsey Stultz go into classrooms every other week for social emotional learning, as well as do short counseling sessions, small groups and interventions.

Wiley said she attributes some of the younger students’ struggles with social emotional skills to masks and not being able to see each other’s expressions. Students also had to be physically more separated from others, not giving the ability to play together as they would have before the pandemic.

Students also were limited to recess with their own class, so they weren’t interacting with as many peers.

The most affected students were the younger ones. Early Learning Center students had to do remote learning. They were also doing social emotional learning for the first time, but behind the computer screen, she said.

“We understood better the importance of just face-to-face contact and being able to have those conversations in person,” Wiley said.

The counselors had always been doing lessons in classrooms, but as the younger kids came back to school in-person, Wiley said they emphasized those skills that were lagging.

Some students struggled with self regulation, body control, managing stress and focus after coming back from online school, Wiley said. These issues go hand-in-hand with both increased technology use at home and possible effects from COVID.

Stultz said she saw increased anxiety, less engagement in learning and issues paying attention.

Class lessons depend on what students are needing, and that’s been the case since before COVID, she said.

Normally a school day is very structured: students go from one location to the next and have transitional periods throughout the day. When learning was all virtual, students had a lot more unstructured time. When class did return to school, students had to stay in their own classes every day and specials like music and phy ed came to them.

With more unstructured time at home, kids had more time for technology or video games, so coming back to school sometimes led to withdrawal from these things, especially with older kids, Wiley said.

The pandemic reinforced the importance that school counselors play in teaching social emotional skills and the value of relationship and connections in the community, not just for students but for everyone.

“I feel like it just makes us more intentional and how we make sure students are feeling connected and getting the support they need,” Stultz said.

Families are also more comfortable reaching out if their child is struggling and needs help, Stultz said. The pandemic has broken down some of the barriers and normalized conversations about student’s struggles, she said.

Elementary principal Seth Heide said although there has always been importance around the connection between students and teachers, the pandemic showed it’s not something you can replicate. Although online learning was what had to be done at the time, it’s clear it’s not as effective, he said.

As some students fell behind in certain social emotional areas, staff worked to backfill those needs in the years that followed.

Academically, students were also slightly behind, but with time got caught up, he said.

“But I think just getting out of the habits of learning was probably the hardest part, just kind of working with a level of rigor that, you know, because we really scaled things down to the simplest terms,” Heide said.

It took time to get students back into the swing of extended periods of learning, he said.

He said while the pandemic showed teachers the possibilities technology has for learning, teachers have gone back to books and physical teaching devices. Having students write with a pencil and paper is something that can’t be replaced by technology, he said.

In the few years that followed the reopening of in-person learning, Heide said he thinks students have been caught back up to where they should be, but they’re always working to make greater gains with new curriculum.

Intentional opportunities for students to enjoy school

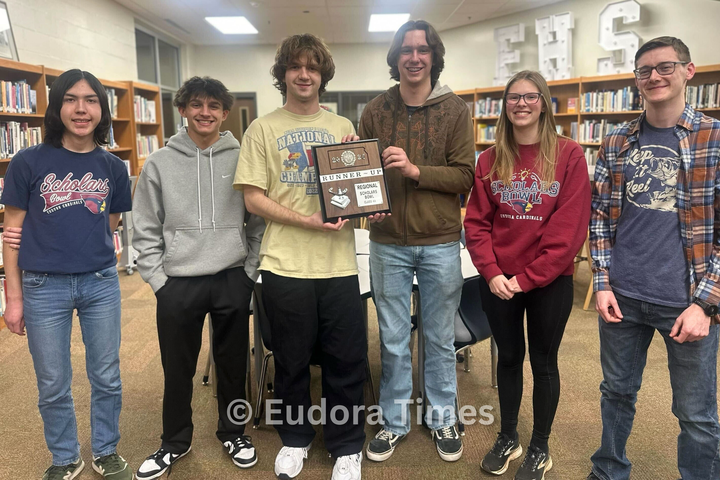

Middle School Principal Jeremy Thomas said family and community involvement has increased since the pandemic. Enrichment clubs like the grill club, no-bake club, and the game and fish cleaning club have increased as well. The middle school has over 20 clubs, with hopes of every student being involved in one. The number participating in mentorship programs has also increased.

“We’ve really put an emphasis on getting kids involved, and we’ve started to see that grow,” he said.

As some scores dropped academically, it required more resources to help kids, and that enabled staff to keep students from falling through the cracks in ways other than just academically, Thomas said.

Thomas agreed the pandemic brought new ways of doing things when teachers were forced to explore new ways to use technology to make class possible, but it also showed them a need for students to get off technology, too. Teachers are wanting to do more hands-on activities to make up for what was missed during COVID.

Students in middle school now were in their early years of elementary school when the pandemic started, so many missed out on learning how to interact and resolve conflicts with other students.

Most students in middle school have phones or social media, and there is more need for strict control on phones in school, he said. That’s also led to more need for other support staff like counselors and a full-time Bert Nash staffer.

Overall, they’re putting more emphasis on looking at the whole student, rather than just test scores or data, he said.

Students who are virtual or who do homeschooling are now able to participate in more school clubs and activities due to the new KSHAA rules established after the pandemic.

Teachers are also valuing their collaborative time to create lesson plans and make sure students are not falling through any cracks, he said.

Older students learning more about issues that affect them

High School Assistant Principal Sean Hayden said students are able to accept and respond to change quicker and easier than adults, but the pandemic was a struggle the further it went along.

“Kids are the most resilient people on the planet,” he said.

The constant changes between virtual, hybrid and in-person classes was hard on students, though, he said.

Hayden said while he thinks they are almost in the clear from lingering pandemic effects, there is still a significantly higher percentage of kids experiencing a rise in anxiety and depression. There is also an increase in technology dependencies, as well as substance addiction like nicotine.

The pandemic was also a civics lesson, not just for students, but for adults, too, he said. More people started to become aware of local government decision making, whether City Commission or School Board.

People want to have their voices heard and be involved with decisions that affect them, he said.

From the teachers’ side, the pandemic increased burnout and was hard on administrators, he said.

The number of students wanting to do virtual classes is going down compared to two years ago, Hayden said.

“Kids want to be here, and they want to be learning in person,” he said.

Standardized testing

The district has been reporting relatively stagnant testing data for several years, Hundley said. That’s not to say COVID didn’t impact students’ scores and learning, though, she said.

“Obviously, across the state, we saw dips. And not to say that Eudora didn’t have a little bit of a dip in that, but it was not as substantial as maybe some other districts experienced,” Hundley said.

According to the state, level one scores on state tests shows limited ability to understand and use the English language arts skills and knowledge needed to be academically prepared for post-secondary success. Level two indicates basic ability, level three shows effective ability and four shows excellent ability.

Here are the 2019 Eudora numbers for math:

23.48% of kids in level one (limited ability)

45.07% of kids in level two

26.20% of kids in level three

5.24% of kids in level four (excellent ability)

Here are the 2024 Eudora numbers for math:

23.88% in level one

41.77% in level two

23.4% in level three

10.92% in level four

Here are the 2019 Eudora numbers for English/language arts:

24.42% in level one (limited ability)

35.74% in level two

20.18% in level three

9.64% in level four (excellent ability)

Here are the 2024 Eudora numbers for English/language arts:

25.23% in level one

38.39% in level two

27.87% in level three

8.48% in level four

High schooler ACT scores averaged 21.4 in 2019 and 21.2 in 2020 and went down slightly to 20.7 in 2021. Scores for 2024 were 19.4 against the 19.2 state average.

There have been statewide changes in students, whether as a result of technology use or from residual pandemic effects, Hundley said.

The pandemic helped lead the district to looking into what instructional resources teachers are using, additional professional development and comfortability with high-quality instruction practices, she said. It also led to the implementation of the new strategic plan.

“I think COVID just provided an opportunity for us to start really re-thinking education and different questions that maybe we hadn’t been asking,” she said.